SpaceX's Starship gets closer to launch—but the future of its Texas Starbase is in doubt

An environmental assessment clears the way for test flights of the giant rocket to orbit, but any missions to Mars may depart from Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

SpaceX cleared another hurdle in its quest to launch its Starship, the world’s most powerful rocket, when the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) granted environmental approval for orbital launches from the company’s site in South Texas. The decision, announced on June 13 after months of delay and debate, requires several actions to ease the impact on public beaches and wildlife surrounding SpaceX’s private spaceport at Boca Chica Beach, 20 miles east of Brownsville, Texas. But the ruling still represents a win for Elon Musk’s space company, which could have been required to complete a much more comprehensive and lengthy Environmental Impact Statement before any orbital launches took place.

Despite the conditional approval for SpaceX, which still needs a launch license for orbital flights, the future of the rocket complex in Boca Chica Beach is less certain than it may seem. The growing facility, known as Starbase, has become the subject of heated debate among state and regional officials who see the site as an opportunity for economic development, environmentalists concerned about the impacts on fragile ecosystems, locals whose community has been transformed, and SpaceX devotees with grand visions of living on Mars.

While the debate goes on, Musk has said that SpaceX plans to ultimately move Starship operations to NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida, where the company is building a new launch tower and already has all the permits required for orbital launches. The South Texas site will likely be maintained as a hub for research and development, but as Starship becomes operational, there will be less need for a vibrant test program at Boca Chica Beach. SpaceX may have won the battle to launch Starship test flights from Starbase, but during the fight, Texas may have lost its claim on future, historic flights to Mars.

To conduct orbital Starship flights from Texas, which would involve launching a bigger rocket than the Saturn V that took astronauts to the moon, the company would need to comply with 75 new provisions. These include limits on road closures and the creation of wildlife corridors, as well as other less conventional requirements such as preparing “a historical context report … of the Mexican War,” before SpaceX obtains the final FAA license to launch its mega-rocket. The document only covers 10 launches per year—five suborbital and five orbital—a limit that the company could easily run into once Starship starts flying. Adding to the pressure in Texas are legal actions by environmental groups, one suit filed and at least one more threatened.

“It’s deja vu all over again,” says Jim Chapman, a board member of the local environmental group SaveRGV (Rio Grande Valley), which is suing the state of Texas over the spaceport at Boca Chica. Chapman says that SpaceX wasn’t ultimately required to adhere to mitigation measures when it began flight tests of the smaller upper stage of Starship, and he is skeptical the FAA will fully enforce the requirements for launching the much larger Super Heavy booster. “I don't see how anything's changed,” he says.

For others, the limits placed on SpaceX and comments from Musk that suggest the company could ultimately move launch operations to Florida represent a lost opportunity to lead humanity’s voyages into the solar system.

“Everybody down here, Brownsville and the whole valley, was expecting to see that this was going to be the Gateway to Mars,” says Louis Baldera, a Brownsville resident who operates the popular streaming site LabPadre, which keeps cameras on the SpaceX site and offers live commentary during times of peak activity. “As far as anything being launched directly to space to the moon or Mars, that’s more than likely not going to happen here. I think that’s going to bum some people out.”

Rocket party foul

Starbase’s precarious future first was revealed during a gathering hosted by Musk at the site on February 10. Beneath a fully stacked, 400-foot-tall Starship rocket, Musk took the stage and showed a video of a simulated launch from Boca Chica Beach, delivering humans from Texas to the red planet.

The South Texas site seemed poised to lead the way to Mars—then Musk addressed a question from a reporter about SpaceX’s construction of a new launch site at Kennedy Space Center. Musk, awkwardly forthright, then addressed “the future role of Starbase.”

“I think it’s well suited to be our advanced R&D location,” he said. “So, it’s like where we will try out new designs and new versions of the rocket.” Reporters exchanged looks and locals shifted uncomfortably as Musk continued: “I think Kennedy will be our sort of main operational launch site.”

The worst fears of South Texas supporters had been voiced. “I didn't know any of those plans beforehand,” says says Jessica Tetreau, a Brownsville city commissioner and passionate SpaceX supporter, who was in the crowd that night. “I’m glad that somebody asked that question because we get a lot of insight. What startled us was when we heard the timeline and how they would have to start moving things to Florida. ... We just knew that we had to work that much harder and that much faster to improve our case that Starship belongs here in South Texas.”

For Dale Ketcham, vice president of governmental relations at Space Florida, the state’s aerospace development agency, Musk’s words came as a welcome confirmation that SpaceX ultimately planned to shift Starship operations to the Sunshine State’s Atlantic coast. “I think there was a certain degree of nervousness on Florida's part, watching Starbase grow and grow,” concedes Ketcham. “But we were always told that the testing would be in Texas and the [flight operations] would be in Florida.”

Even so, the idea that Boca Chica Beach would become the Gateway to Mars has been associated with the site since its inception. At the 2014 ribbon cutting, Musk positioned the spaceport as a place where history would be made.

“It very well could be the first person to go to another planet could launch from this location,” Musk said. “This is really going to be a new kind of spaceport that is optimized for commercial operations.” In December 2020, after the high-altitude flight and crash-landing of a prototype called SN8, he tweeted: “Thank you, South Texas for your support! This is the gateway to Mars.”

If SpaceX demotes its Texas spaceport to a research facility, an economic benefit will remain from the demand for skilled workers. But there are an estimated 1,600 employees at the Starbase facilities, and some of the jobs may be moved to Kennedy Space Center.

“In 2013 we were named by the U.S. Census as the poorest city in America, and that was ironically the same year that SpaceX selected this location for the next launch site,” Tetreau says. “It really feels like destiny, like something that was always meant to happen, like they were always meant to come here and save us from that situation. And they absolutely did … I just hope that we can continue that momentum and not lose any jobs to Florida or have to relocate any of these families.”

Rocket factory hurdles

Throughout 2021, politicians debated the benefits of the launch complex, lawyers dueled over regulations, and environmentalists raised concerns about how the giant rocket factory and growing launch site would impact wildlife. All the while, SpaceX doggedly constructed an elaborate launchpad at Boca Chica, including a 480-foot-tall launch tower. Musk has nicknamed the tower Mechazilla due to two beefy robotic arms that the company plans to use to catch the giant boosters as they land at the same pad they launched from. “Ready to refly in under an hour,” he tweeted.

A shift occurred in April 2021 when NASA awarded SpaceX $2.89 billion to develop a version of Starship to use as the lunar landing vehicle during the first crewed return to the moon as part of the Artemis program. NASA’s Space Launch System rocket and Orion capsule will carry the astronauts to lunar orbit, where they will board a waiting Starship vehicle that will ferry them to the surface.

This role in NASA’s moonshot pushed Starship operations toward Kennedy Space Center, home to NASA's human spaceflight operations since they began. Work there has ramped up during the FAA certification at Boca Chica Beach. The first three legs of another Mechazilla launch tower have been raised, and the other three lie nearby ready for installation. Tents have sprung up that mirror the ones in Texas where Starships are built. And just like in South Texas, the foundation of a massive and permanent “starfactory” to build even more rockets has been established.

Musk always had plans to develop a Starbase launch site in Florida, but when SpaceX decides to do something on a timeline, the dirt flies quickly. “They started work on Pad 39 three years ago, but only in the last nine months has it really started accelerating,” Ketcham says.

Beyond Musk’s public statements, SpaceX hasn’t commented on the future of Starship operations. The company declined a request for comment for this story, and a tweet on SpaceX’s feed saying, “One step closer to orbital launch,” has been the only official comment on the FAA’s recent decision.

But the renewed construction in Florida speaks volumes. “I'm not one to say I know what Elon's plans were; they're wonderfully opaque as a corporation,” Ketchum says. “I'm sure that the lander contract and the challenges with the environmental assessment at Starbase had something to do with it.”

SpaceX is not known for its patience. During the public event in February, Musk warned that the FAA delays could lead to Starship’s first orbital flight happening outside Texas. "We do have the alternative of the Cape," Musk told the crowd, referring to Kennedy Space Center. "We actually applied for environmental approval for launching from the Cape a few years ago and received it." He added that it would only take until fall 2022 to ready the site for an orbital launch.

That may be overly optimistic, as Musk’s predictions tend to be. SpaceX’s complex at Kennedy Space Center is the sole launch site of the Crew Dragon capsule, which is the only spacecraft currently available to deliver astronauts to the International Space Station. That makes the launchpad a national asset, and not one to be used for experimental flights. The idea of testing a massive booster on that same launchpad is giving NASA and Space Force officials some pause, given the explosive results of other early SpaceX tests.

“They blew up a lot of Starships in Texas,” Ketchum says. “And blowing stuff up—or, ‘unplanned rapid disassemblies’—you can do them in Texas, but the neighbors get kind of fussy about that at the Cape.”

That may preserve Starbase as the place to create the launch system, failures and all, while Florida is steadily developed for safer mission operations.

“I think everybody would like to see SpaceX be able to continue to develop Starship, and the sooner the better,” Ketchum says. “Florida is confident that we’ll get a lot of work regardless of how much of the testing is done in Texas.”

Plovers and floating spaceports

As Florida becomes a new Starship hub, the obstacles SpaceX faces at Boca Chica Beach are piling up. Not everyone is thrilled to have the region be relegated as the preferred location of fiery crashes.

The FAA’s environmental assessment included negative feedback not just from locals, but from federal agencies including the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Documents obtained by CNBC showed FWS found a decline in endangered piping plovers around Starbase and cited potential harm to other shorebirds and sea turtles should the spaceport expand. The findings are likely to fuel legal challenges from environmentalists. In May the Sierra Club and the Carrizo/Comecrudo Tribe of Texas announced they were joining a lawsuit initiated by the local group SaveRGV.

The suit, filed in October 2021, is not against SpaceX, but the Texas General Land Office, its commissioner George P. Bush, and Cameron County for allowing the company to close the public beach for tests. Texas officials, as they were luring SpaceX to build a spaceport in 2013, amended the state’s Open Beaches Act to exempt counties used “for space flight activities.” The environmental group is claiming the amendment violates the state constitution.

“Our position from day one was just this expanded SpaceX project has enormous environmental consequences,” Chapman says. The lawsuit seeks to force SpaceX to perform a comprehensive Environmental Impact Statement, which would likely take more than a year to complete.

The pushback is already having an effect as SpaceX scales back its ambitions in Texas. The company sent its most recent proposal for the Boca Chica facility to the FAA in September 2021. At that time, it said it wanted to build a power plant, natural gas processing facilities, and water infrastructure to create freshwater for the launchpad deluge systems used to put out fires.

But the FAA says SpaceX removed its request to construct some of this infrastructure, including a desalination plant, natural gas pretreatment system, and power plant, “in response to public and agency comments and other developments.” Some of those projects are optional—the desalination plant can be replaced with water trucks—but the loss of those facilities reduces the utility of Starbase as an orbital flight center.

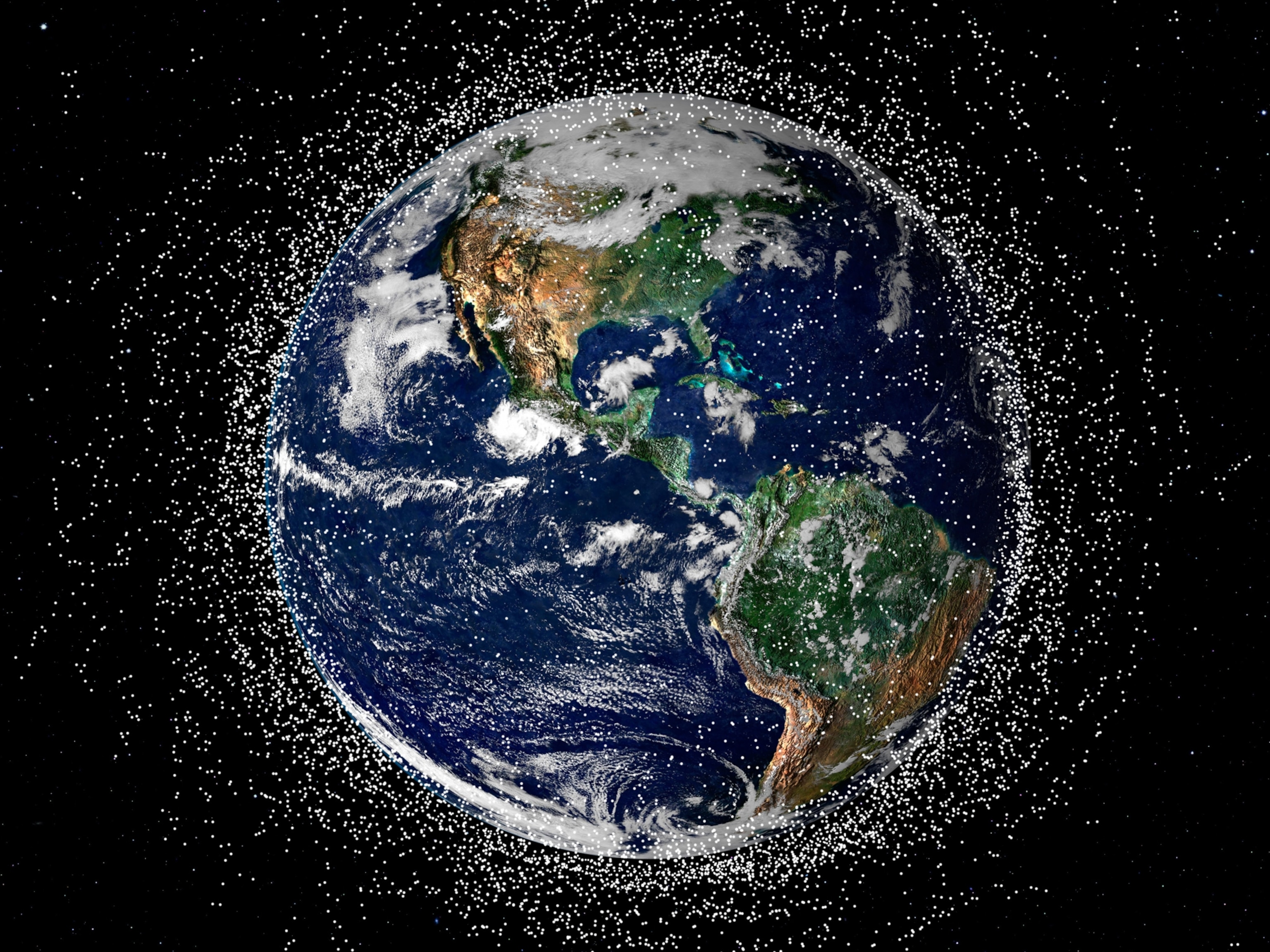

In addition to the launchpad in Florida, SpaceX may attempt to conduct launches offshore in the Gulf of Mexico. In Mississippi’s Port of Pascagoula, two oil rigs owned by SpaceX, called Phobos and Deimos after the moons of Mars, are being converted into Starship launch platforms. These platforms could host the risky launch tests that Kennedy Space Center can’t support.

"Over time I think there's going to be floating spaceports," Musk said in February. “We've got these two converted oil rigs that are going to be turned into orbital launch sites, and they can be moved around the world.”

Musk idealistically envisions a thousand Starships leaving Earth every two years, when Earth has close encounters with Mars, to facilitate humanity's first permanent migration to another planet. With such a cadence, Texas, Florida, offshore platforms, and elsewhere may be needed to truly settle the red planet.

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Orangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first timeOrangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first time

- What La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planetsWhat La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planets

- This fungus turns cicadas into zombies who procreate—then dieThis fungus turns cicadas into zombies who procreate—then die

- How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?

Environment

- What La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planetsWhat La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planets

- How fungi form ‘fairy rings’ and inspire superstitionsHow fungi form ‘fairy rings’ and inspire superstitions

- Your favorite foods may not taste the same in the future. Here's why.Your favorite foods may not taste the same in the future. Here's why.

- Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?

- The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?

History & Culture

- Meet the ruthless king who unified the Kingdom of Hawai'iMeet the ruthless king who unified the Kingdom of Hawai'i

- Hawaii's Lei Day is about so much more than flowersHawaii's Lei Day is about so much more than flowers

- When treasure hunters find artifacts, who gets to keep them?When treasure hunters find artifacts, who gets to keep them?

Science

- Why ovaries are so crucial to women’s health and longevityWhy ovaries are so crucial to women’s health and longevity

- Orangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first timeOrangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first time

Travel

- 5 of Uganda’s most magnificent national parks

- Paid Content

5 of Uganda’s most magnificent national parks - On this Croatian peninsula, traditions are securing locals' futuresOn this Croatian peninsula, traditions are securing locals' futures

- Are Italy's 'problem bears' a danger to travellers?Are Italy's 'problem bears' a danger to travellers?