Winston Duke's mother wanted him to be a pastor. In one of our first conversations, he told me she was still holding out hope, imitating her thick Tobagonian accent: “‘Maybe you’ll still become a preacha!’” He playacts his loving but firm rebuff: “Lady,” he laughs, “give it up!”

For a certain kind of mother, and a certain kind of upbringing, a job in the church is the highest calling. That Duke’s older sister graduated from high school early and eventually became an accomplished doctor didn’t really ease the pressure, either.

Duke, thirty-six, is no man of the cloth. But he has a creation myth to share when I arrive at the Shulamit Nazarian gallery in Los Angeles on a hot, sunny Tuesday afternoon. On display are fifteen works from the artist Trenton Doyle Hancock, who dreams up alter egos, villains, cartoonish Klansmen, and Technicolor creatures, conjuring a world from inspiration that’s part autobiography and part fantasy.

There’s something in these provocative pieces that captivates Duke. He asks the gallerist to pull a small comic—a primer on Hancock’s work—for me to look over. The last time he was here, the gallerist replies, Duke received their final copy. So he says he’ll educate me himself, opening a book of the artist’s materials: “These,” Duke points at two ink-and-paint-drawn figures, “are the father and mother of pretty much everything in his world. The father had an affair with the flowers. He—”

The gallerist jumps in: “He masturbated in a field of flowers.”

A few weeks earlier, Duke spent two hours walking through the gallery accompanied by Hancock and his wife, the artist JooYoung Choi. “He spoke about the work almost as if he was in the studio with me when I made it,” Hancock tells me later. “He was able to speak about a layer of the work that I normally don’t get to talk about with people.”

Duke and I pause in front of one of his favorite pieces. It’s from a series by Hancock inspired by the work of Canadian American painter Philip Guston, who portrayed Klansmen in mundane contexts, such as riding around in a car smoking. Hancock riffs on the theme, depicting himself holding out a Klansman’s hood to his own alter ego, Torpedoboy. Instead of featuring a mythic battle of epic proportions—like, say, a Marvel movie—the series shows Hancock trying to goad Torpedoboy into stepping on a stool to change a light bulb, with the intention of slipping a noose over him. Duke likes the way you can only see the scene clearly head-on. From any other angle, the work looks like a wall of shaggy fur with random negative space.

He sees a reflection of his own lived experience standing in this spot. “Navigating a lot of these spaces as a Black person, people don’t understand what you’re going through,” he says. You feel it, but it’s difficult to explain in small pieces. Like Hancock’s work, it must be faced dead-on.

“I won’t tell if you touch it,” he stage-whispers, extending a hand to touch the art himself.

The gallery feels like a lesson but also a test, a way to see if I’m just indulging a curious actor’s hobby. Duke is tall and commanding; he laughs big and easy. But if I agree with him, he wants to know why. If I see something he doesn’t, he wants to see it, too. Have I noticed how Hancock’s work is ink-drawn but also collage but also mythic but also lifelike?

What Duke appreciates about this art is that it’s so mutable. So busy, but open. “I just love that it gives you permission that nothing that you think is too much,” he says. “And if you’re in spaces that make you feel as if it is, it’s probably not a safe space.”

Hancock works with paper, canvas, ink and paint, sculpture and video, and felt. Duke’s tools are different—a script, a set, blocking, and a camera. I offer that, unlike actors, artists working alone have no limits. Creation for them is a solo endeavor.

He considers this. “That’s kind of a trap, that we feel like, because they’re generative, they have the most permission,” Duke decides. “We all do. Even though I’m a collaborative artist—I can’t do my work without the writer, director, all the people—I have just as much creative right as this guy,” he says, gesturing at a Torpedoboy portrait. “I just have to find it.”

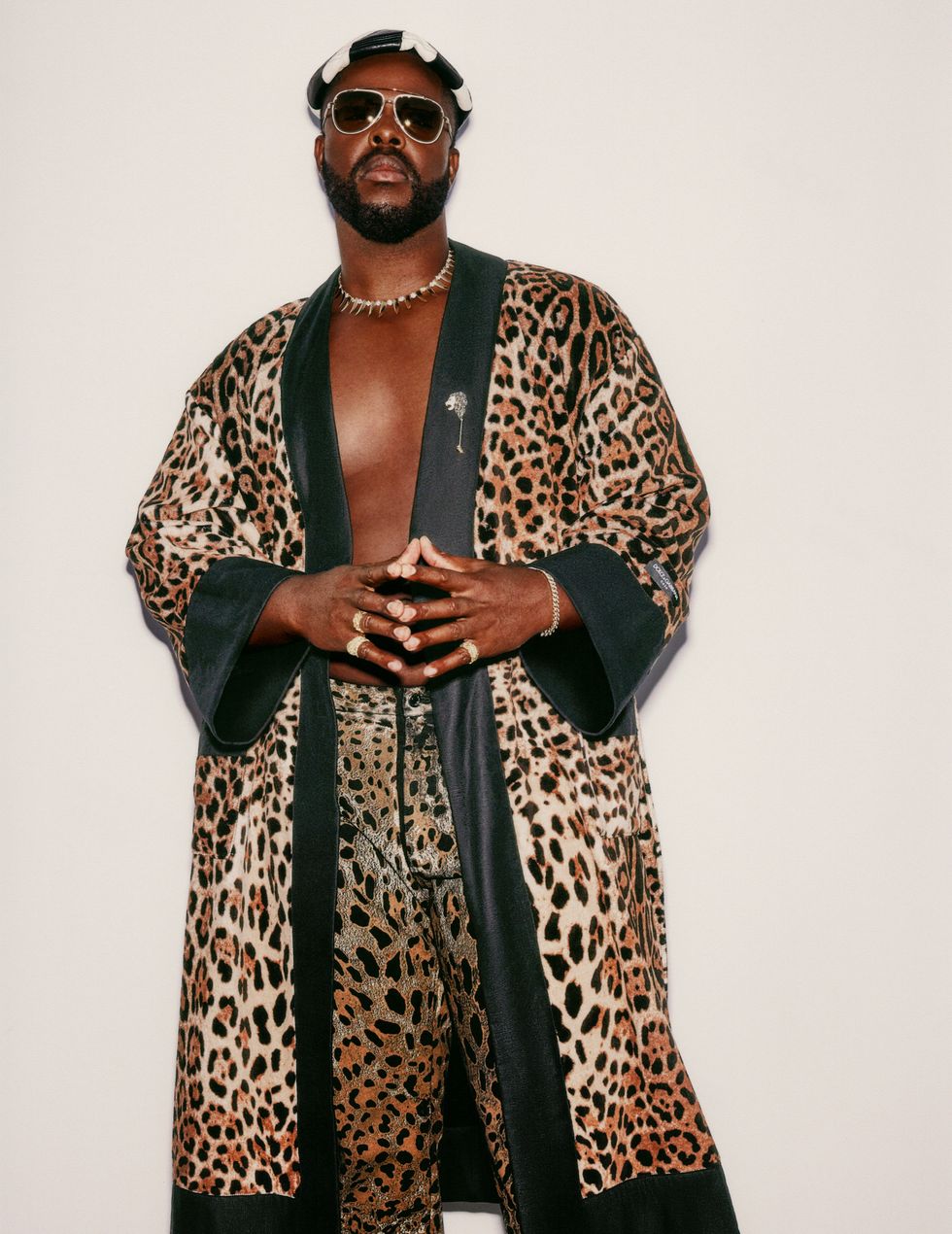

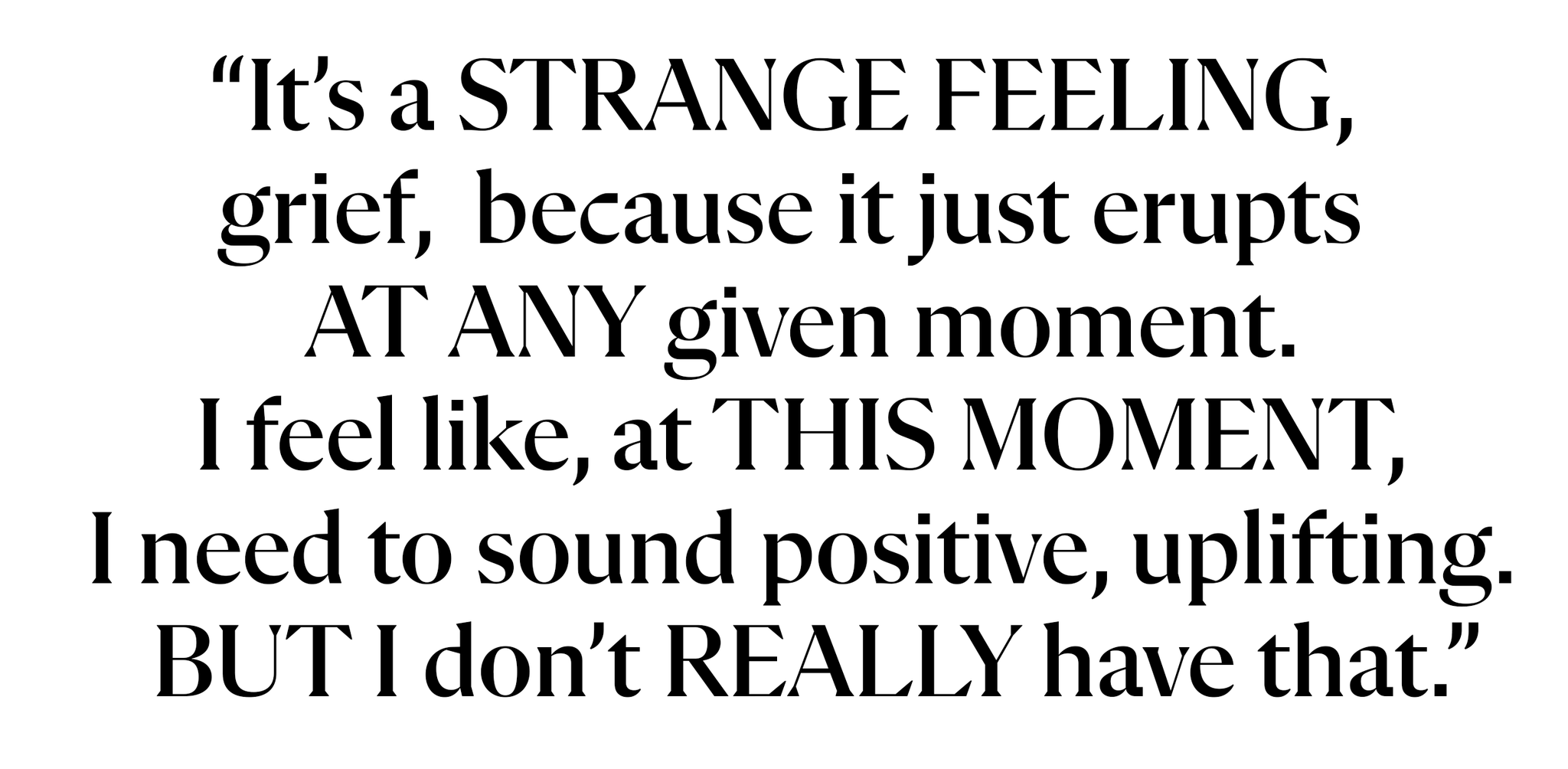

Over the past few years, success has found Duke suddenly, and in a big way. His breakout role in Black Panther made him a wanted man in Hollywood. (Starring in a film that brings in well over $1 billion at the box office tends to do that.) And his part in the sure-to-be-massive, just-released sequel, Wakanda Forever, will raise Duke’s profile even higher. For an actor looking to harness his powers fully, both ubiquity and artistic fulfillment loom: He’s working with name-brand directors and participating in Rihanna’s latest star-studded Savage X Fenty fashion show. Everything is happening for Duke, all at once.

But it’s a moment shaded with grief. Chadwick Boseman’s surprising 2020 death hung over the production of Wakanda Forever. And just a month before the biggest film release of Duke’s career, his mother and closest confidante, Cora Pantin, his beloved “Mama Coco,” also died unexpectedly. Now, as Duke ponders what he wants his own future to look like—which of the enviable options in front of him to choose—he must navigate that path, for the first time, on his own.

When Black Panther introduced audiences to the fictional African nation of Wakanda in February 2018, it became an outright phenomenon. It was a Marvel movie with real cultural resonance—historical significance, even. It was also, you know, just a really good watch. The cast included Oscar winners (Lupita Nyong’o, Forest Whitaker), sex symbols (Michael B-is-for-bae Jordan), saints (Boseman), and Hollywood royalty (Angela Bassett). But Duke, playing M’Baku, the charismatic and domineering leader of the taciturn Jabari tribe, was the obvious breakout.

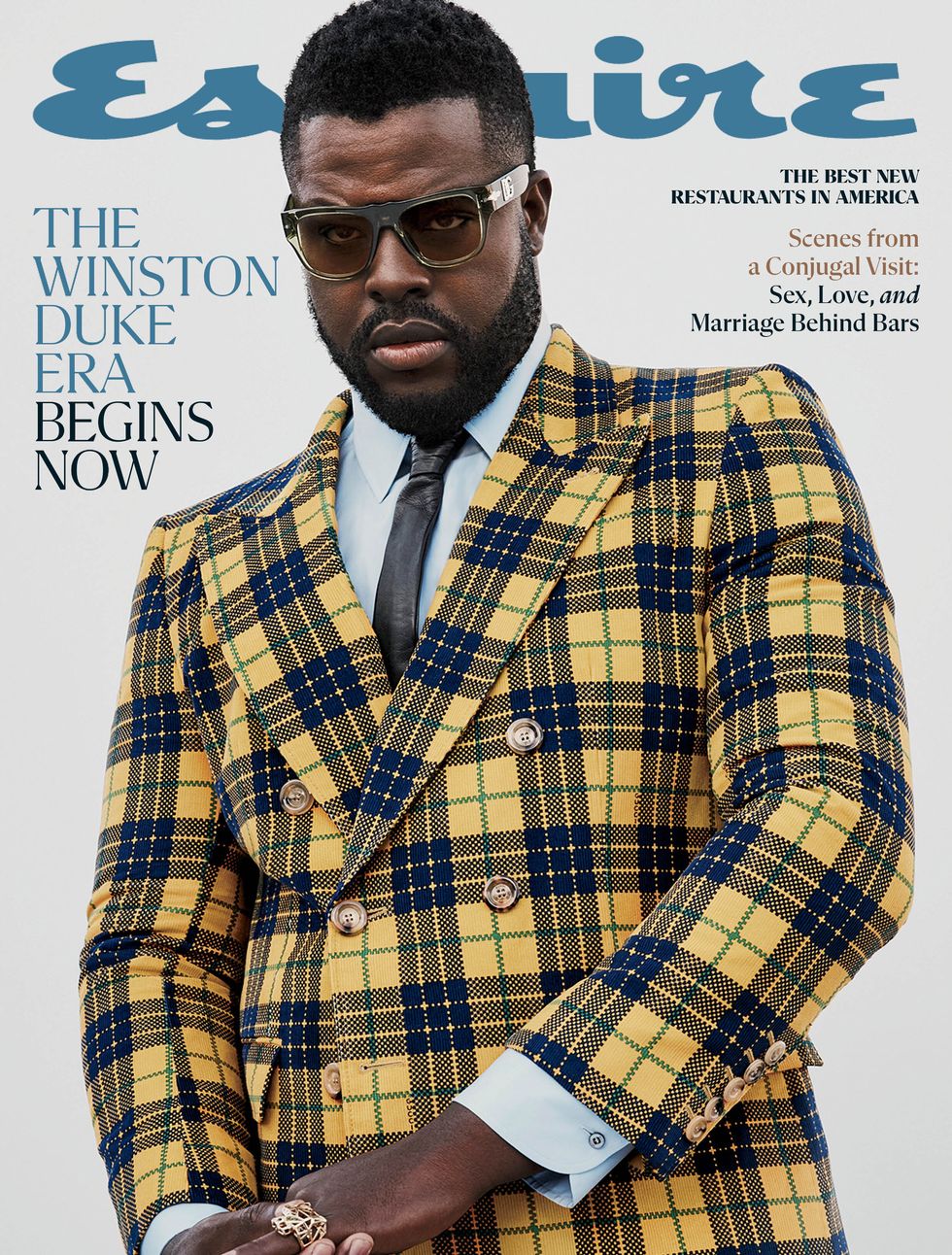

This article appeared in the Winter 2022/23 issue of Esquire

subscribe

He made for a surprising usurper—a little-known Yale graduate in his very first film role. Duke was “funny, shameless, imposing (imagine if Orson Welles joined the W.W.E.),” The New York Times observed, adding his name to its critic’s list of the year’s best performances. And his sex appeal sizzled. “M’Baku could blow my m’back out if he wanted to,” a polite request for more thirst traps from Duke, went viral more than once.

Black Panther became the critical darling of the Marvel Cinematic Universe, inspiring memes (“Wakanda Forever” but also “Ruthkanda Forever”) and earning seven Academy Award nominations, including one for Best Picture. A Black blockbuster had never existed on this scale. Just a few scenes made Duke an overnight celebrity. “It was a watershed moment. It shifted conversations,” the actor says of the first movie. “And it focused on a spectrum of Blackness, characters from all walks of life, every skin hue.”

Post–Black Panther, he got to prove he was more than a formidable alpha. In Us, Jordan Peele’s Get Out follow-up, he starred as Gabe, an upper-middle-class dad in a Howard University sweatshirt on the run from his tortured doppelgänger. “Winston was up for the challenge of subverting the perceptions of M’Baku, presenting Gabe by playing a more vulnerable and fallible dad,” Peele says. In the Sundance indie Nine Days, he was a middle manager working in a kind of purgatory, interviewing unborn souls to decide if they get to have a life on earth. The director of that movie, Edson Oda, wanted to find a different sensitivity. “You don’t expect that this big, imposing figure is afraid of living,” Oda tells me. “But inside we all can be vulnerable.”

Duke gravitates toward stories that feel otherworldly or extreme—that he’s a Marvel actor with indie ambitions is too simplistic a narrative. The Mark Wahlberg–Peter Berg movie Spenser Confidential might be the one exception on paper, but its production was still enriching: “He had not done a lot of film work, but in a way, it was like watching hazing at a fraternity in a college,” says Spenser costar Alan Arkin. “He’d come out of a very serious several years of studying at Yale. And he had to be thrown into the kamikaze world of the kind of film we were in.”

“I want to lean in to what I consider the epic,” Duke says. “Black Panther’s an epic. I look at Nine Days as an epic. Us is an epic, the proportions and the scale. It’s that the world is ending, or that the stakes of the situation require major transformation to get through.” He has a foot in both the Marvel and DC universes: He voiced Bruce Wayne in Batman Unburied, a psychological-thriller caped-crusader podcast produced by Spotify that taped while he was working on Wakanda Forever. “He was M’Baku from Wednesday to Friday,” says creator David S. Goyer. “And Bruce Wayne–slash–Batman on Saturday and Sunday.”

But it’s M’Baku who gets him recognized, and M’Baku who pays his bills. After the gallery, we wait outside for an Uber to take us to lunch at Holloway House. A passerby recognizes him: “You’re that guy,” he begins,“from the movie. Mmmm . . .”

Duke nods. “M’Baku, yeah.”

Inside he is Winston, an art fanatic, chatting with the gallerists; out here on the sidewalk he is the Marvel hero, doing his civic duty. He looks at me expectantly; the fan hands me his phone to snap a few photos.

Much hangs in the balance, however, with Marvel’s most acclaimed franchise. Boseman died of colon cancer in August 2020 at the age of forty-three. His death coincides with his character’s, a decision that continues to cause controversy with fans. When Wakanda Forever starts, King T’Challa has died offscreen, raising questions as to who will sit on his throne and don his Black Panther suit—not to mention who will anchor the series for years to come.

Duke grew up in Tobago, the smaller island in the Caribbean nation of Trinidad and Tobago, living right on the water in the town of Argyle. “He was very free-spirited,” his older sister, Cindy, remembers. Their mother was one of twelve children, so they had a large extended family of playmates and adventurers. (Duke does not have a relationship with his father.)

Pantin moved her family to Brooklyn when Cindy said she wanted to be a doctor. Winston was nine, suddenly a latchkey kid in a big city. In the early days, with his mom working long hours, the energetic preteen was eager to prove his independence, especially walking alone to P. S. 91, a public school in Crown Heights. “We would let him head off, but me and my mom would follow and make sure he really was going where he needed to,” Cindy says.

The family decided it would be safer for Duke in Rochester, where Cindy moved, just a few years later, to study at the University of Rochester’s medical school. He moved in with her in 2001, while he was in high school, and found that he was more comfortable outside the big city. He wrestled and played football and had a growth spurt. “It was a closer match with how his life started out,” Cindy says of their life in Rochester. “It helped him reconnect with an aspect of our identity.” Pantin would take a 5:00 p.m. bus from N.Y.C. on Friday and spend the weekend parenting, cleaning, and cooking. She then took a 1:00 a.m. bus back to Brooklyn to make it to work on time come Monday morning.

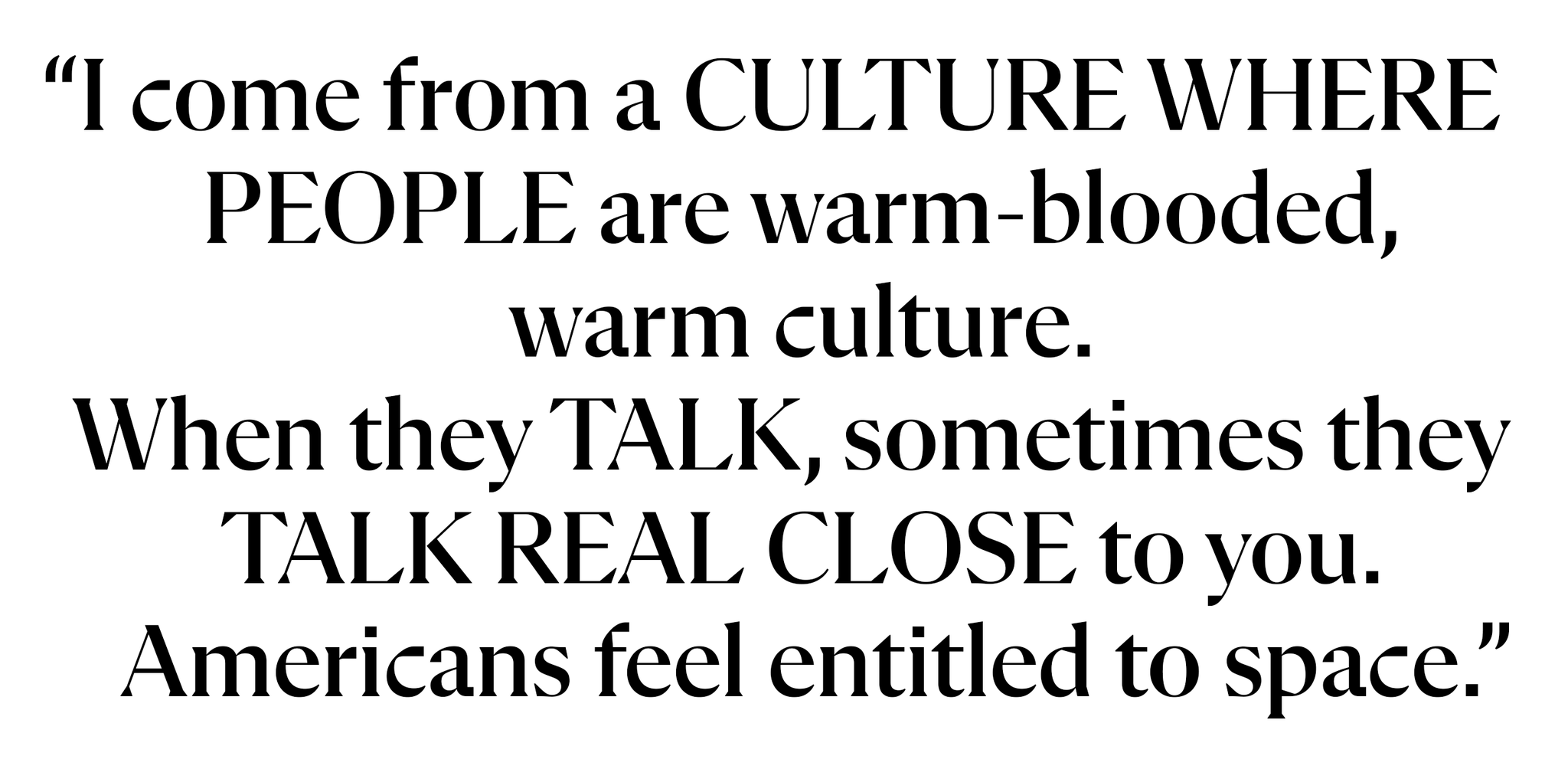

“I never had this, like, teenage angst. I did go through bouts of teenage depression,” Duke recalls. As an island kid, he missed warm weather. Rochester was cold, and Americans were colder. “I come from a culture where people are warm-blooded, warm culture. When they talk, sometimes they talk real close to you. Americans feel entitled to space.”

A high school Spanish teacher caught on to Duke’s performative streak—he came alive when he had to speak in front of the class. His first role was in a school sketch-comedy show: “I literally had all my lines written on my hands,” he says. He played it as part of the joke. At seventeen, his sister remembers, he had a friend drive him to a casting call at a mall in nearby Pittsford. He won. “He felt like this was the universe telling him, ‘This is your career. This is for you,’ ” Cindy says. “He immediately started talking about wanting to move out to California.”

The family appreciated art but had traditional, practical jobs. In Tobago, Pantin owned a successful restaurant, and Duke’s cousin founded a political party. Cindy is a Johns Hopkins–and Yale-trained physician. Acting wasn’t out of the question, but the family had its requirements. “We felt strongly that you need to have a fallback,” Cindy says. “And so the discussion was, after college, if California is where you wanna go, we’ll explore that.”

After graduating from the University at Buffalo with a theater degree, he took the LSATs. But when the family moved to Baltimore for Cindy to start training at Johns Hopkins Hospital, he had second thoughts. “‘I really don’t feel this law school thing, Mommy,’” Cindy recalls him explaining. “He looks at me, and he says, ‘This isn’t me.’ ” Once he got into Yale, Duke explains, his mother accepted it, saying, “Well, they know Yale in Tobago!”

Duke entered the Yale School of Drama looking for an actor’s rubric: What could he do to guarantee a good performance every time? He wrestled with impostor syndrome, feeling self-conscious. “I was not one of the class favorites.” He got supporting roles that he tried to make centerpieces instead.

His frequent, and current, costar Lupita Nyong’o was in the class above him. “He was extremely bold,” she tells me. “I remember just being dwarfed by how much of a risk-taker he was.”

The good people at Axe Ventures in Hollywood, a hatchet-throwing spot on Vine and Fountain, promise to limit the number of puns, but it’s part of the deal. For less than a hundred bucks, we get seventy-five minutes and a variety of sharp stuff to throw, with “Beware of axe-idents,” “Axe me if you need any help,” that sort of thing, peppered in. In a big store-front in a nondescript business park, behind an El Pollo Loco, there are nine lanes. It’s our next stop after our post-gallery lunch detour. Duke isn’t recognized but he’s not not recognized. Another thrower happily deputizes herself as the joint’s maître d’ to help us fill out the waivers.

No less than five minutes in, Duke is back in teaching mode. He’s already withstood too many of my pitiful tries and even more pitiful errors. But he’s a patient, gracious tutor. When I’m not getting it, and continue not getting it, only to still not get it, he records dozens of videos of my attempts. We review the film together.

“Much better!” he says about one near hit. “Less energy, too.”

Duke strikes a naturally imposing figure. M’Baku announces his dominance in his chest-forward stance, and in the way that his thighs sprawl beyond his throne and he barks commands. But Duke’s style is built around his easy affection. He wants to share, enjoy, relax with you. He’s eagerly curious and never satisfied, never defeated. (He wants to have selected the best activities for this piece, and he probes me for info about who’s outdone him.“I went to Italy with the cast of Succession,” I offer, “and a cat café with Jason Derulo.” To the latter, he responds, “It was a little weird, huh?”)

“I don’t like this one as much,” I say, in my begging-to-take-a-break voice, retrieving the mini tomahawk I threw moments ago that didn’t stick.

“You like the heavy one?” Duke replies.

It’s my sixteenth toss in about as many minutes, but he won’t stop recording me until we both get the shot. Once I make one, I default to relief, Duke to delirium. No one cheers louder, and soon our throwing neighbors join in. We graduate to two separate lanes when someone leaves. And without the, let’s say it, burden of instructing me, Duke suddenly morphs into the mighty warrior he plays onscreen. He throws—and lands—two tomahawks with one hand.

Duke couldn't find the words. At a service for Boseman, he remembers, there was an attempt to do a “Wakanda” chant as a send-off for the actor, but it didn’t feel right. “It just was like, ‘Leave that outside,’ you know? The moment was begging you to leave it outside and be in the moment here,” he says. The service was a shocking juxtaposition: Boseman’s family, friends, and widow, all crying; it was in the first year of the pandemic, with everyone masked and trying to stay at a safe distance. “It was emotionally intimate. You needed to be held, but you’re trying to do all the social distancing.” The scene left him bewildered. “It hurt really bad just seeing how small the box was. I was standing there in complete disbelief saying, ‘Where’s the rest of it? Where’s the rest of everything?’”

Boseman had become a major star, and Black Panther was his identity and mission. “When he passed away,” Duke says, “[the sequel] was supposed to start shooting in a month or two.” Marvel maps out its releases years in advance; there’s complicated jargon for how every movie and TV release interacts within an even more complicated multiverse. (The super-deluxe Avengers: Endgame, in which Duke makes a brief appearance, was part of Phase 3. Wakanda Forever is the last film of Phase 4; the already-announced Phase 6 plans include a movie slated for release in the spring of 2026.) Black Panther director Ryan Coogler had a T’Challa-focused script that had to be completely rewritten.

Whether or not to replace Boseman was the subject of much external debate. #RecastTChalla trended online after a trailer for the sequel was shown at Comic-Con in the summer of 2022, while a Change.org petition tried to pressure Marvel into doing the same, suggesting that the best way to honor Boseman would be to keep his character alive without him. Duke—as well as the Black Panther creative team—didn’t agree, and he addressed the decision on the podcast Jemele Hill Is Unbothered in an episode released the day prior to our meeting. Before we start axe throwing, I hear him playing clips on his phone, monitoring the reaction online.

Duke seems frustrated by the fans’ petulance. The decision not to hire another actor to play T’Challa was made with respect for Boseman, and in a time of grief. Instead of acknowledging that, he says, “they center their own need for a character when none of this would be possible if the people who brought this to life didn’t participate, from behind the scenes to in front of it.”

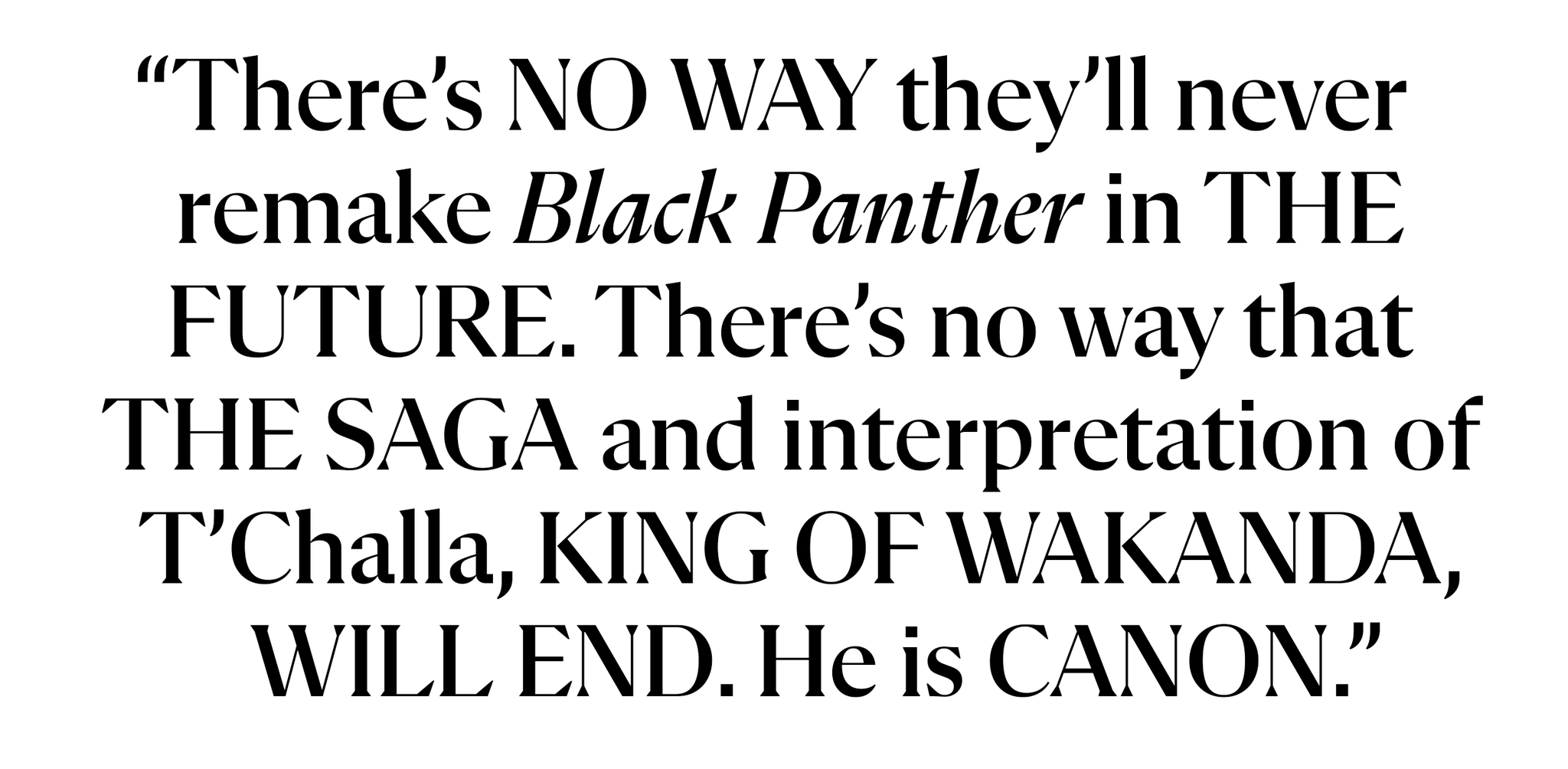

What’s more: Comic-book movies play with timelines and multiple universes constantly. Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021) features three Spider-Men! Upward of forty people have played or voiced Batman over the past twenty-five years, including Duke. T’Challa will, in another universe or in another story, almost certainly return. “There’s no way they’ll never remake Black Panther in the future,” Duke says. “There’s no way that the saga and interpretation of T’Challa, King of Wakanda, will end. He is canon. So trust that it’ll come. But allow this to be a human experience.”

A day later, Duke and I meet for dinner. He selects Mélisse, the four-dollar-signs-on-Google tasting-menu restaurant led by two-star Michelin chef Josiah Citrin. There are five tables and an interior that is dark and chic modern but also vaguely resembles an Amex Centurion Lounge. Every course is elaborate: a golden osetra-caviar “deviled egg,” charcoal-grilled Japanese amadai, celtuce with dulse seaweed sauce, something small and gold-leaf adorned that I’m instructed not to nibble at but to eat whole. There’s a lo-fi playlist from a DJ physically swapping out records on a turntable per song; we go from Anderson .Paak to Phil Collins.

“My first year or two years in this country were defined by sleeping on floors. I never expected anything to be handed,” Duke says. “To be dining with you in a restaurant doing a tasting menu is insane.” He’s back to being curious, asking for detailed feedback with every bite. His current workout regimen—he wants to look good on this cover!—means he’s mostly cut out alcohol, but he joins me for the wine pairing.

We’re talking about loss, which runs both through and around Wakanda Forever. When fans return to the African nation, it will be different from what they remember: In the wake of T’Challa’s death, the region is fractured, though M’Baku has remained a presence. “We would talk about the character as a walking stress test,” Coogler says of working with Duke on the first movie. “[M’Baku] is the guy who’s going to poke at the foundation and make sure that it’s stable. If it’s not, he’s gonna call it out.” In the sequel, M’Baku spends much of the movie nudging Shuri, played by Letitia Wright, to refocus her efforts on leading Wakanda instead of avenging her family.

On set, Black Panther producer Nate Moore says Duke was meditative, “I think because he uses so much energy in his performance that, like a boxer, between takes he rests and resets before getting back out for the next take and delivering the goods.” For the actor, it was important to be patient as well as generous. “There was recognition of shared trauma. You could look across and say, ‘Danai [Gurira] is going through something similar; I’m not the only one having this. Letitia’s going through something similar, and I can feel it.’ ” For everyone, he says, “there was always the willingness to be more patient, the willingness to be patient with the creative team, with Ryan, with this very unique situation that no one could control.”

The actors grieved privately, but other on-set happenings made their way into the press. In October 2021, it was reported that Wright expressed her anti-vaccine stance openly to the cast and crew. Her injury on set in Boston further delayed production. Before the final two courses, I ask him about it. “One, it’s not anything that’s ever come up,” he begins. “It’s also not anything I’ve ever seen or experienced any problem with her on set. Other than third-hand reports in the media, I never even knew she had this position.” It’s not quite thirdhand, I remind him: Wright shared an anti-vax video on Twitter.

“There wasn’t anything where it was like, ‘We can’t do something today ’cause Letitia can’t be here,’” he says. “We’ve never had an on-set problem with Letitia and her alleged stance.”

Though Wright’s Shuri dons the Black Panther suit in this movie, it concludes with a cliff-hanger—and those of you who haven’t yet seen the film and don’t want to know the ending may want to move right along to the next section. Still here? Okay: Shuri travels to Haiti to spend time with Nakia (Nyong’o) and misses what would be her coronation. Instead, M’Baku is there. In her absence, he’s king and ruling over all of Wakanda. “M’Baku is unapologetic. Very proud. A bit conservative,” he says of the ending. “It’s kind of a shocking and, for me, very exciting moment. I get to wonder now what kind of king he will be.”

Since Duke had to make his supporting characters at Yale “very feature,” I ask how he feels now that M’Baku, a side character, is front and center.

“I don’t like to think of it that way,” he says. “I don’t agree that it’s in any way mine. Both Black Panther movies are really defined by its ensemble. And it was forced to be defined by its ensemble. When you lose your titular character, it was then placed on the shoulders of the group to pull the story together.”

He adds that he doesn’t know what’s in M’Baku’s future. “The power of what Marvel has become is that it doesn’t belong to any one actor or anyone lead or character.” Does he think the fans know that? “If they’re paying attention, they’ll see it.”

But Duke’s life, with a major role in an iconic Marvel franchise, will change even further. At dinner, he allows that this moment will open up more doors. It’s like the Hancock art we saw the day before: It will give him more room to be permissive in his art and his life. “I could be more experimental. I could be playful. I could be more independent in some of my choices,” he says. It will help him promote nonprofits such as Partners in Health, the global organization for which he serves as a celebrity ambassador. Also, Duke likes nice things. “When I first started interior decorating, I always wanted to have a place that felt like a magazine,” he says. Beautiful statement pieces, minimalist execution. But then it happened. “And I just couldn’t live in it!” he adds with a big, throaty M’Baku laugh.

Around 4:00 a.m. on a Friday in October, two days after our dinner at Mélisse and just hours before the scheduled photoshoot for this story, Duke was woken up by his sister. Mama Coco had died at age sixty-six.

“A lot of painful events ensued, including seeing her body that morning, getting there while she was still warm in the ICU, and hugging and kissing her body until it got cold in our arms,” he tells me less than three weeks later.

His voice sounds smaller over the phone, quiet; he talks slowly. Not like he’s choosing the right words but like he’s trying to find any at all. “Everyday’s been a really big challenge. Every day has been filled with a lot of grief, a lot of grief while trying to still be functional and live in a world that still has a lot of expectations, especially around professionalism. A lot of people from the outside don’t really understand how much of a toll it takes on you,” he says.

Shortly after we first met, Duke said he wasn’t really into doing press. He’s fine with attention ebbing and flowing. He doesn’t always feel like being a professional personality. But now he seems desperate to compensate: a few words about how he’s holding up, about the movie, about how much he misses his mother. This crowning moment has changed for him. Wakanda Forever is a rumination on loss—that has more significance now. He has less patience for people who’ve wanted to rush to recast Boseman. The pain is compounded onscreen when another major character dies, too. “It’s going to be very hard for me to watch. I can tell you that right now,” he says dryly.

He and Cindy are staying close in this moment. She accompanies her baby brother to the rescheduled photo shoot in late October. “This is totally uncharted territory,” she tells me later. “[Our mother] showed us to be present. She showed us that in times of grief, you honor the departed by trying to remember the goodness, trying to remember what made them special, but also looking for the goodness in each other.”

But the load is heavy. “No one is praying for me like that anymore. There’s so much grief. It’s a strange feeling, grief, because it just erupts at any given moment. I feel like, at this moment, I need to sound positive, uplifting,” he says, his throat catching. “But I don’t really have that. What I can say is that I miss the best person that I think I’ve ever known so far in my life.”

With this new movie, and this role, the world is coming to Duke now, and he’s harnessing all his artistic might in return. Pantin wanted her son to be a pastor, but this moment is the culmination of her prayers.

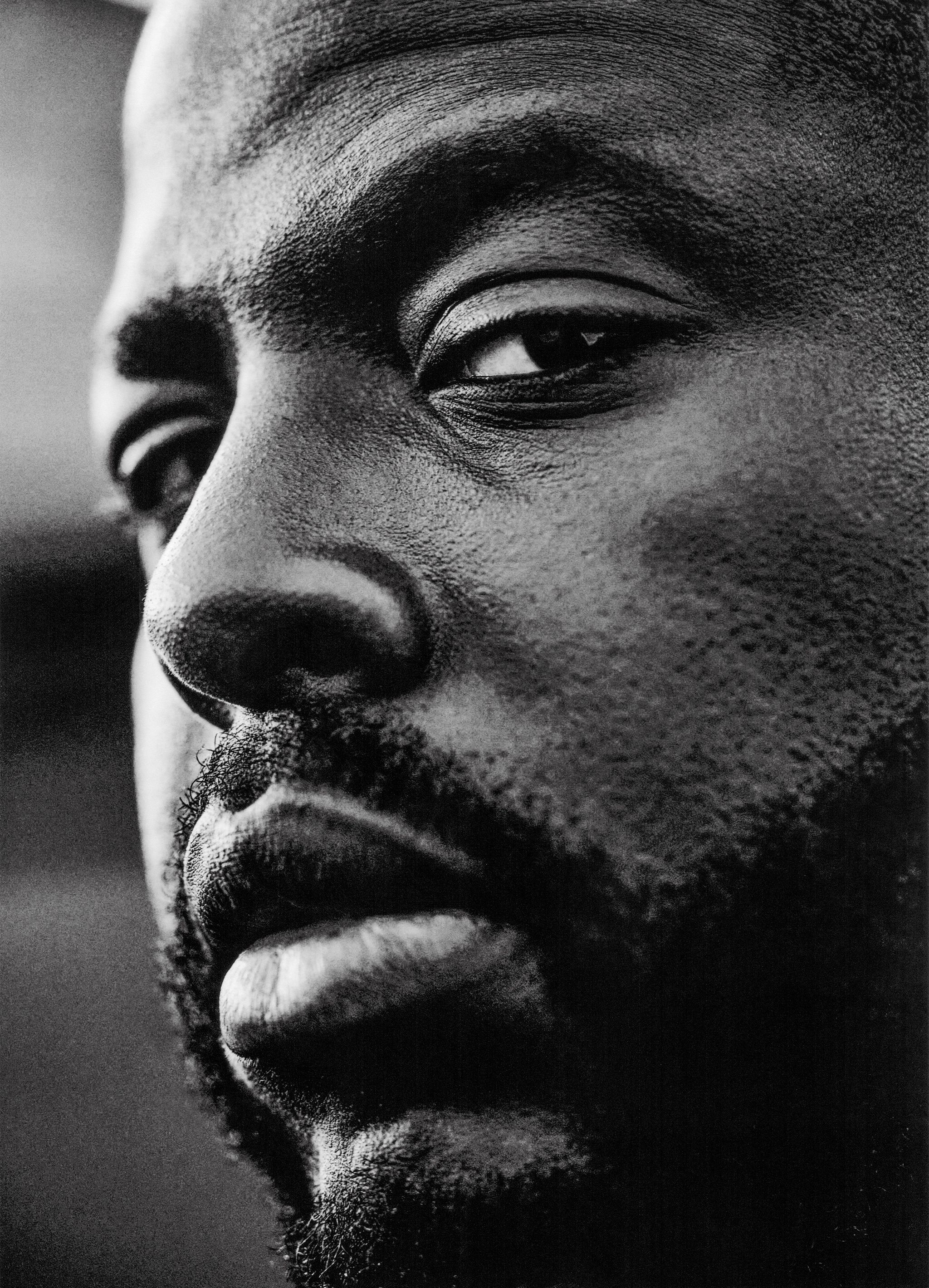

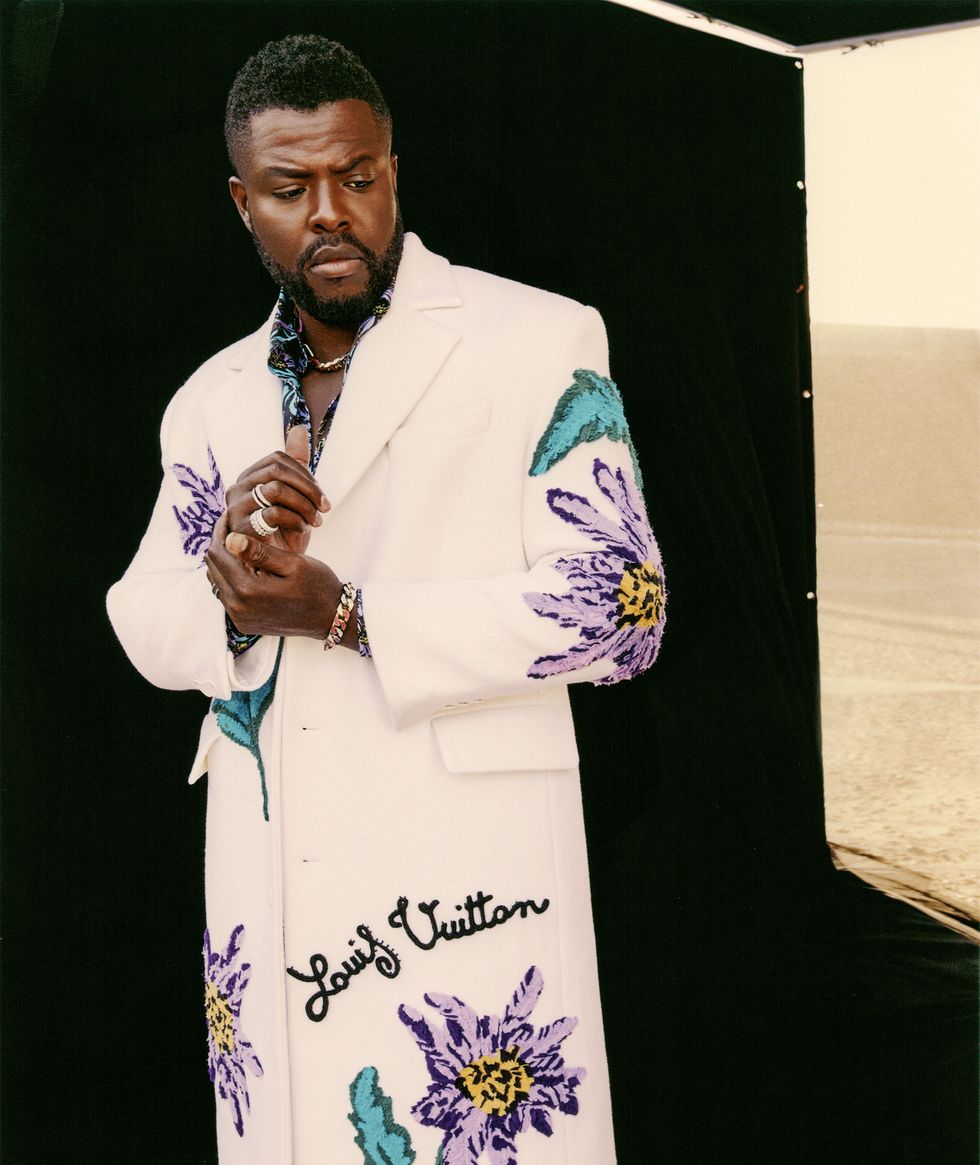

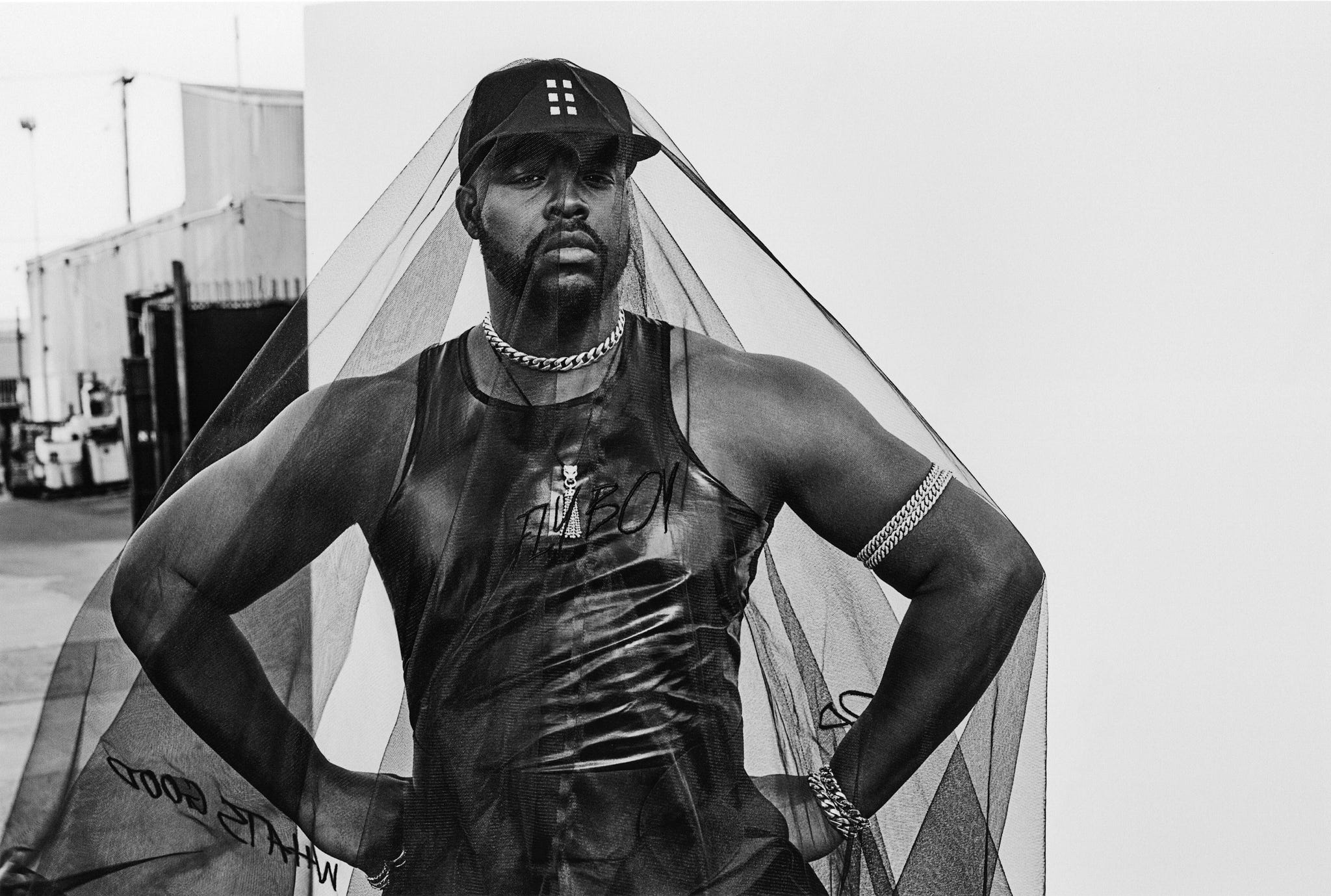

Photographer: AB+DM

Stylist: Andrew Mukamal

Market Editor: Alfonso Fernandez Navas

Groomer: Risha Rox

Barber: Goose

Design Director: Rockwell Harwood

Visuals Director: Justin O’Neill

Executive Director, Entertainment: Randi Peck

Executive Producer, Video: Dorenna Newton

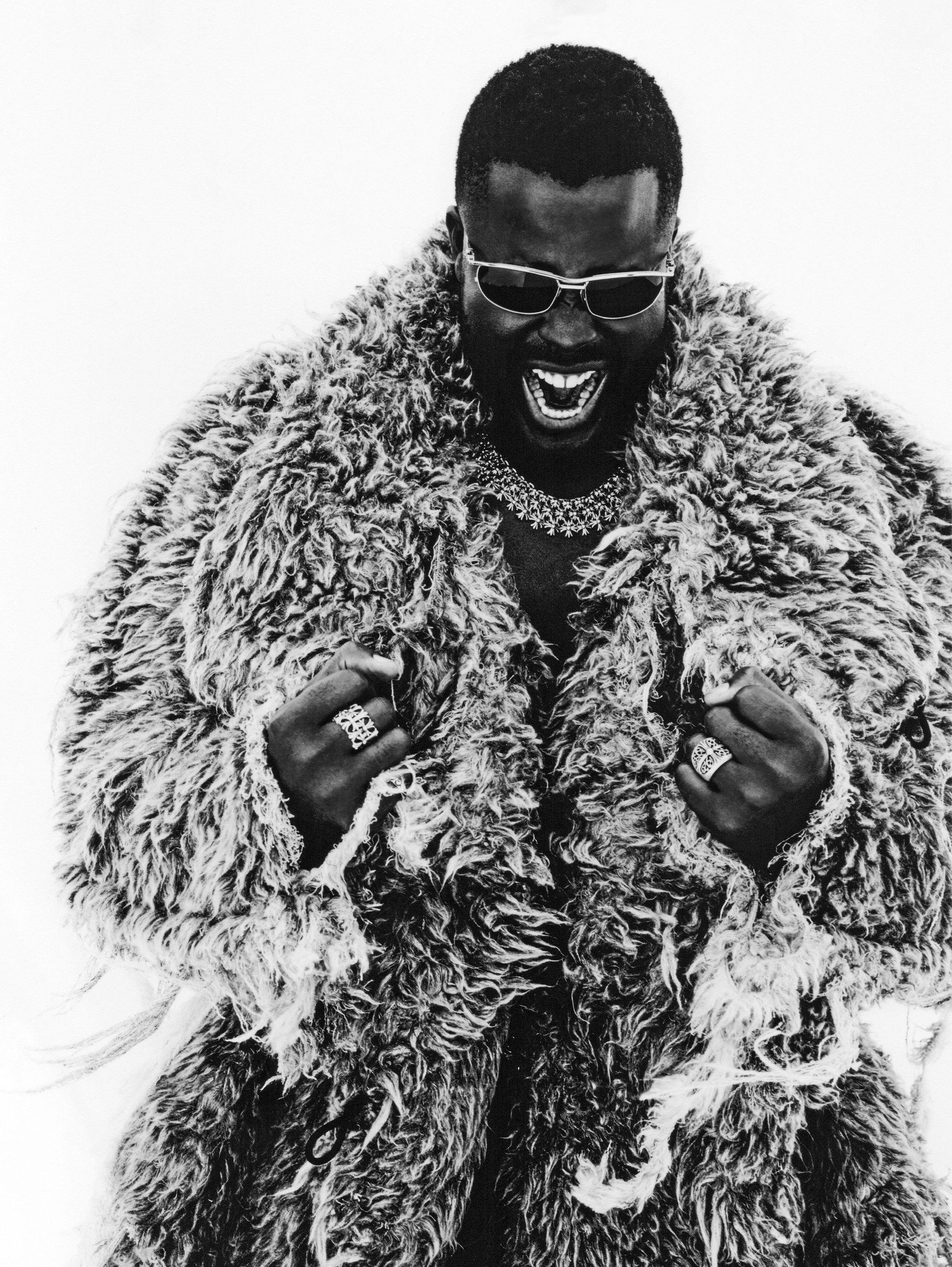

Additional Fashion Credits: In the opening photo, coat by Diesel, necklace and rings by Chrome Hearts; in the video, knit vest by Pierre Louis Mascia, pants and bracelet by Louis Vuitton Men’s, sneakers by Balenciaga, necklace by Cartier, ring by Bernard James, ring by David Yurman, ring by Veneda Carter.